Dozens of palm oil licenses in West Papua were revoked in mid of 2021. Amidst the climate crisis mitigation, the licenses revocation seems like an oasis in the scorching desert. There is a new hope to indigenous people for a sustainable management of their customary land. But, what will happen after the revocation?

Palm oil license review gave positive result after spending three years of evaluation. Since 2018, the license review team made coordination with various ministries and institutions to evaluate 24 corporation’s licenses. The results of evaluation were presented in a closed door meeting in the end of February 2021.

“We hope the follow-up of the process could provide significant encouragement to the indigenous people to manage their natural resources in West Papua,” said West Papua Governor Dominggus Mandacan in a coordination meeting on the Results of Palm Oil License Review at the West Papua Governor office on Thursday, 25 February 2021.

Read also: Jayapura Court Gave Another Rebuff to Palm Oil Lawsuit

License review uses Plantation Business Assessment (PUP) as the assessment instrument. For a company that has run its production, the evaluation team applied an Operational PUP. Meanwhile, when the company is on construction process of palm oil plantation, Development Phase PUP was applied.

License revocation

“The assessment result shows that all concessions of palm oil plantations had committed administrative and operational faults,” said Darkono Tjawikrama, EcoNusa’s Coordinator of Research and Geospatial. Those frauds included the implementation of conservation principle of sustainable palm oil plantation development as the criteria stipulated by Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and Indonesia Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO).

There are 24 palm oil plantation companies in West Papua with around 759,000 hectares of concessions. As from the figure, around 625,000 hectares are forest areas. However, not all concessions has been planted. As from around 400,000 hectares of active concessions, palm oil-planted areas are only 134,000 hectares.

Following the evaluation, 8 regents revoked 16 licenses of palm oil companies covering 340,000 hectares. The revocation does not only give good news in terms of climate crisis mitigation, but also of community sovereignty in equal and sustainable management of natural resources.

Read also: EcoNusa CEO: Returning Rights to Indigenous People Should Come after License Revocation

West Papua government has taken swift measures to return the concession areas to the indigenous people. Around 7 months after the license revocation done by 8 regents, Dominggus Mandacan issued a Governor Regulation of West Papua No. 25/2021 on the Designation Procedure of Indigenous People and Customary Land Recognition.

“The Governor Regulation is intended as the guideline for a designation of indigenous community and customary land. Hence, the indigenous community will have legal basis to manage their own customary land which used to be the palm oil concession areas,” said Darkono.

Article 4 of the Governor Regulation No. 25/2021 stipulates provincial and regency/mayoralty governments to establish a committee for indigenous community. The committee is assigned to identify, verify, validate, and designate indigenous people and customary land. The identification of indigenous people is done upon considering the history, location and size of areas, traditional law, traditional administration system, and traditional stuffs.

One of the regions that has performed the Governor Regulation No. 25/2021 is Sorong Regency. The formation of committee is based on the Decree of Sorong Regency No. 224/Kep. 408/XI/Tahun 2021 on the Committee for Indigenous People in Sorong Regency. To perform its duties, the committee members consist of academician, traditional law expert, non-governmental organization, and indigenous people.

Read also: Long Road (to Run) behind Victory

“We do it step by step. The most important is mapping (of customary land), and then government recognition should be given to the indigenous people officially. They (indigenous people) will understand their own rights,” said Sorong Regent Johny Kamuru after the EcoNusa Outlook 2022 in early March 2022.

Local capacity building

Johny said that after the indigenous people officially get their rights of customary land management, the government of Sorong Regency will provide capacity building to the indigenous people. He cited an example such as organic farming as one of the programs. “The farming program will help them increase their income, despite the small amount but it is sustainable,” he said.

Concerning the capacity building program, EcoNusa has School of Eco-Involvement (SEI) program. SEI educates local development cadres to shape up social justice. This is done by producing cadres who care about village development.

Read also: EcoNusa Outlook 2022: Approach of Rasa for Eastern Indonesia

Up to December 2021, SEI has been held in Sorong Regency, Merauke Regency, South Halmahera Regency, Seram Bagian Barat Regency, Kaimana Regency, and South Sorong Regency. As from the 6 regions, 64 villages had taken parts in the SEI programs in which 158 village heads and 146 local cadres chipped in.

The learning program during SEI was adjusted to the local condition. In Merauke Regency, the class was categorized into database program and organic farming program. Cristofora Kwerkujai, an SEI participant from Erambu Village in Merauke, studied the organic farming and she could earn extra income for saving from selling her crops.

Meanwhile, Billy Matemko, a villager of Bupul, learned about database as the basis of village development. Billy collected social, sectoral, and spatial data. Social data deals with demography with more in-depth level. In addition to demographic data collection, the database team also collected data on the number of people in a household, sex, education, occupation, and blood type education, health, up to system of village administration.

Read also: Reorganizing Village in Merauke Based on Data

The sectoral data is required to analyze food production with the surrounding ecosystem. For instance, data on the size of area, type of soil, weather, water resource, available vegetation medicine, historical and cultural sites, traditional legacy, traditional arts, and road network.

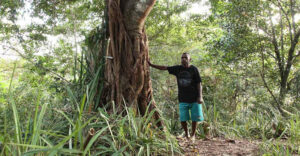

Spatial data has crucial role to the community, particularly in Bupul Village which is surrounded by palm oil planation concessions. With spatial map, the community could have knowledge on the local potential and defend their customary rights. “Because there is life in the forest. There are natural resources such as fish, meat, medicine for the people. There are many hidden things we do not know yet. So, if there is a development, the community understands which part that should be granted,” said Billy.

Editor: Leo Wahyudi