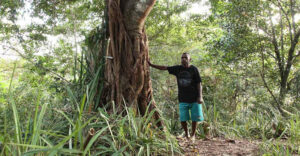

In Kais Darat District, South Sorong, Southwest Papua, the forest is home to a variety of trees, birds, and other animals. The forest is also a place of livelihood for the Nakin Onim Fayas sub-tribe. For them, the jungle is a supermarket because it holds food, medicine, and building materials.

Even though logging companies once entered and young people started leaving the village to look for work in the city, the elders still strive to protect their forest. “If this forest is damaged, what will we pass on?” This question was posed by one of the elders during the Customary Forest Management Workshop in Hohore Village, Kais Darat District.

Read Also: Sago Forest Ecotourism in Kais: Exploring Papua’s Ecosystem, Culture, and Cuisine

During the event, customary elders, mothers, fathers, and young people held a meeting in the village hall. They sat in a circle discussing how the forest has protected them and their desire for the forest to remain intact. The forest is not for sale, because it is where they get their living, especially from hunting and harvesting sago.

Thus, with assistance from EcoNusa, the idea emerged to form a Social Forestry Business Group (KUPS) for the Wild Boar Trade within the Customary Forest Scheme. They agreed to name the KUPS Boow Wanu Beta, which comes from the local language of the Maybrat tribe, the origin of the Nakin Onim Fayas sub-tribe. Literally, boow means goods/property, wanu means all of us, and beta means together or in togetherness. Combined, Boow Wanu Beta can be interpreted as “This property belongs to all of us.”

The Philosophical Meaning of Boow Wanu Betae

There is a philosophical meaning in the name Boow Wanu Beta.

First, this business is a collective property, not belonging to individuals, the management, the village chief, or customary figures. Boow Wanu Beta belongs to the entire Nakin Onim Fayas customary community. All parties—women, men, youth, and elders—have equal rights, responsibilities, and benefits from this endeavor.

Second, it builds a sense of shared ownership and responsibility. “This property belongs to all of us” is also a reminder that the success of the business depends not only on the KUPS management but on the active participation of the entire community: hunting wisely, protecting the area, recording transactions, managing finances, and distributing sales proceeds fairly.

Read Also: Lingkar Jerat Papua Cooperative is Ready to Produce Quality Wild Boar Sausages

Third, it is a symbol of customary community sovereignty. Boow Wanu Beta is also a clear statement that the customary community has the right to design its own business model, based on their customary values and laws. This is a form of customary economic sovereignty. A business that grows from their own land, managed in their own way, and whose results are for their own generation. With the name Boow Wanu Beta, the Wild Boar KUPS is not just an economic means, but also a symbol of unity, a tool for empowerment, and a legacy of customary values. This venture is expected to be a bridge between local wisdom and economic progress, without abandoning cultural roots.

Customary Forest-Based Business Model

Together with facilitators from EcoNusa and the Office of Environment and Forestry, the community began to draft a customary forest-based business model. They created a customary wild boar trade system with regulations that they had agreed upon through generations. These include a mandate not to hunt carelessly, requiring the establishment of a no-hunting zone and a utilization zone. Sales proceeds must also be divided according to customary agreement, with every transaction recorded by the village youth.

Read Also: Deer, Income Potential and Pest at Guriasa Village

The KUPS Boow Wanu Beta began production activities on May 27, 2025. The KUPS buys fresh wild boar meat from the customary community at Rp30,000 per kilogram. The meat is then sold to the local market or to consumers who come to purchase it at the weighing house—the KUPS’s product weighing and sales center—for Rp50,000 per kilogram. This business model not only provides economic value for the group but also contributes directly to increasing the income of the customary community through a mutually beneficial partnership. Since its start until now, they have successfully produced 1,008 kilograms of wild boar meat.

The business is indeed small, unlike palm oil plantations or mines. But the hope is that the proceeds will be enough to cover needs. Children can go to school, houses can be renovated, and, of course, the community can continue to use the forest as a source of livelihood and a home for various types of plants and animals. Two months after the business began, the forest remains green, and the Birds-of-Paradise still dance in the morning. But what has changed is the community’s self-confidence. They are no longer passive guardians of their customary land but active participants in development based on identity and nature. Sustaining the village doesn’t mean selling off their ancestral inheritance. Because nature and humanity can walk together, protecting and supporting each other.