Papua is writing a new chapter in its economic history. After decades of being an arena for natural resource exploitation, a movement has emerged that places nature and Indigenous communities at the center of development. This approach, known as the restorative economy, seeks to heal the environment while strengthening local livelihoods.

A new report titled “Mapping, Needs Assessment, and Pathway for a Bio-Restorative Economy in Tanah Papua” by Kopernik and the EcoNusa Foundation captures this growing movement and its remarkable potential.

“The restorative economy is not merely a conservation project—it is a path toward building a just, prosperous, and sustainable future for the people of Papua,” the report states.

Read the full report here: Mapping, Needs Assessment, and Pathway for a Bio-Restorative Economy in Tanah Papua

Despite its abundant natural wealth, Papua remains trapped in inequality. According to data from Statistics Indonesia (BPS) 2024, the mining and quarrying sector contributes 18.7% to Papua’s regional GDP, yet the poverty rate remains high at 18.1%.

Meanwhile, the Human Development Index (HDI) in several areas, such as Papua Pegunungan, is only 53.42, among the lowest in Indonesia. Dependence on extractive industries has also left deep ecological scars—around 35,000 hectares of forest were lost in 2024 alone, contributing to 480 million tons of CO₂ emissions over the past two decades.

“The extractive model has triggered displacement, loss of livelihoods, and the exclusion of Indigenous communities from decision-making,” the report notes, citing findings from the Agrarian Reform Consortium (2024).

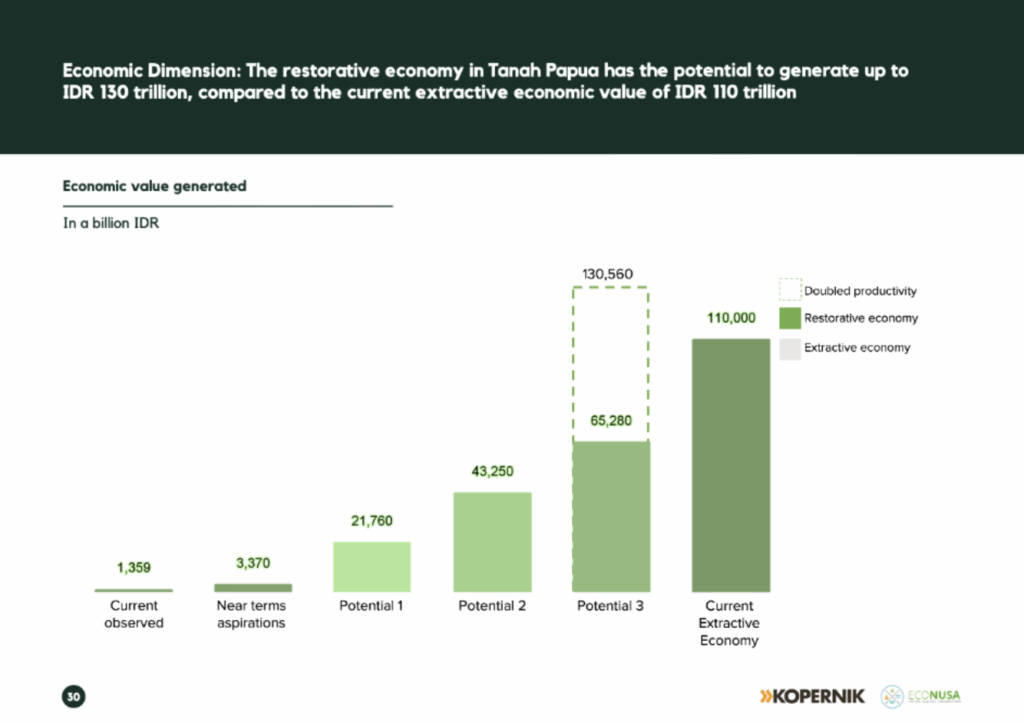

The Potential of the Restorative Economy: IDR 130 Trillion per Year

Unlike the old model of mining and logging, the restorative economy focuses on planting and regenerating. Based on Kopernik’s research, existing initiatives across Papua currently generate around IDR 1.4 trillion annually, involving more than 10,000 people most of them Indigenous Papuans (OAP) and protecting 1.1 million hectares of forest.

In the near term, local organizations aim to expand their operations to reach IDR 3.4 trillion per year and protect 2.7 million hectares of land. If scaled up across the region, the potential value of Papua’s restorative economy could reach IDR 65–130 trillion per year, engaging over 520,000 people and protecting 9.2 million hectares of forest.

“With bold investment, Papua’s restorative economy can grow from pilot initiatives into a provincial economic driver potentially surpassing the extractive industries,” the Kopernik–EcoNusa report asserts.

This movement is anchored in six key commodities managed by Indigenous communities and local organizations: cocoa, coffee, copra, nutmeg, sago, and seaweed.

In Biak, Kopernik has supported seaweed farmers to revive production, enabling them to sell 1.5 tons of dried seaweedto local markets. In Pegunungan Bintang, coffee cultivation has become a vital source of livelihood for remote Indigenous communities despite limited market access.

“The high price of cocoa offers a significant opportunity for Indigenous farmers to strengthen their economy while protecting forests,” said a Kopernik research representative.

Other programs include EcoNusa’s initiative to secure fair prices for copra farmers and KALEKA’s work to open international markets for sustainable nutmeg products. In many villages, Indigenous women lead sago processing, reinforcing food security and embodying ecological sovereignty.

The restorative economy has already shown tangible welfare impacts. According to the report, current activities generate incomes 170% above the national poverty line, and even 7% higher than Papua’s minimum wage.

Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) such as cocoa, copra, honey, and sago contribute over 77% of the sector’s economic value, while fisheries and horticulture play a crucial role in strengthening food security across coastal regions.

“These community-based products offer scalable, long-term income sources while supporting land restoration,” the report highlights.

Despite its vast potential, the report emphasizes that the restorative economy cannot thrive without strong cross-sector collaboration.

“The restorative economy will only grow if governments, the private sector, financial institutions, Indigenous communities, and civil society organizations work together,” it notes.

There are three foundational pillars that must be strengthened for the restorative economy to take root and endure in Papua.

1. Strengthening Local Capacity

Sustainability lies in the hands of Indigenous communities as direct stewards of natural resources. Yet many still face barriers in knowledge, technology, and market access. Therefore, technical training, business management, product processing, and marketing programs must be expanded significantly.

Kopernik stresses that capacity-building should go beyond skill transfer—it should also strengthen local governance systems, including establishing Indigenous cooperatives, reinforcing village institutions, and building locally managed value chains.

“Without adequate capacity, communities will remain mere suppliers of raw materials rather than key players in value-added economies,” the report warns.

2. Inclusive Financing

Financing is another major challenge. The restorative economy requires long-term investments with high initial risk, demanding flexible and inclusive funding mechanisms. The report estimates that up to IDR 2.8 trillion is needed to scale its impact across Papua.

This funding is not only for production but also for essential infrastructure such as rural roads, storage facilities, processing centers, and internet access to strengthen supply chains.

Inclusive financing also means opening opportunities for cooperatives, customary institutions, and micro-enterprises to access capital without heavy requirements. Donors, governments, and the private sector are urged to develop green financing and blended finance schemes that favor local communities.

“Funds must flow directly to the communities—not stop at intermediaries,” the report emphasizes.

3. Policy and Governance Reform

The restorative economy cannot thrive under policies that still favor extraction. Thus, the report underscores the need for governance reform: recognizing customary land rights, simplifying permits for community-based enterprises, and enforcing environmental regulations against industrial violators.

Equally important is integrating the restorative economy into regional development plans and government programs (RPJMD and sectoral strategies) so it does not rely solely on short-term projects.

“Public policy must create space for this new economic model—one that prioritizes regeneration over exploitation,” the Kopernik–EcoNusa report asserts.

These three pillars are interlinked: without capacity, financing is ineffective; without financing, capacity cannot grow; and without protective policy, progress can vanish overnight. The success of Papua’s restorative economy, the report concludes, is not only measured in trillions of rupiah but in building a new order where nature, people, and the economy grow together in harmony.

Five-Year Roadmap: Hope Growing from the Roots

Kopernik–EcoNusa report closes on an optimistic note, presenting a Five-Year Roadmap for Papua’s Restorative Economy—a plan that outlines not just economic targets but also social and ecological strategies to restore balance between people and nature.

The roadmap stands on three key steps:

- Participatory mapping of customary lands.

This ensures that Indigenous communities maintain control over their ancestral territories. Through participatory mapping, customary boundaries are defined based on local wisdom and traditional governance. This process is not merely technical but political—it restores authority to communities long marginalized by top-down development models.

- Policy advocacy.

Without supportive policies, the restorative economy risks remaining rhetoric. The report calls for regulatory alignment between local and national levels—from recognizing customary land rights to simplifying community business permits and protecting key ecosystems. Policy advocacy also aims to embed the restorative economy into regional development documents and public financing schemes.

- Sustainable financing.

This model requires long-term investment rather than short-term aid. Kopernik and EcoNusa urge the creation of a green financial ecosystem, involving Indigenous cooperatives, local financial institutions, philanthropy, and private sector actors committed to sustainability. Through this model, profits circulate within communities, returning as capital, training, and well-being rather than corporate dividends.

“This approach transforms Indigenous communities from aid recipients into key economic actors,” the report concludes. “They are no longer the objects of development, but the subjects driving the restorative economy from the ground up.”

More than an economic study, this initiative is social and ecological experiment in Eastern Indonesia. Papua is proving that prosperity does not have to come from mining, palm oil, or logging but can grow from the roots: from sago gardens, cocoa beans, seaweed harvested by coastal women, and forests that remain standing.

“Through ecological regeneration, social justice, and community-based economic development, Papua has the potential to become a global example of how human well-being can coexist with environmental restoration,” the report declares.

In a world increasingly threatened by climate crisis, this model offers a new kind of inspiration. If successful, Papua could become a “living laboratory” a place where Indigenous wisdom, science, and public policy converge to build an economy that thrives in harmony with nature.

With the right support adequate funding, inclusive policies, and strong cross-sector collaboration Papua has the potential to become Indonesia’s pioneer of a green, just, and community-driven economy.