The workshop Building a Restorative Bioeconomy in Papua: Indigenous Rights, Sustainable Nature, and Shared Prosperity, held at Hotel Vega, Sorong, became a strategic forum to chart the future direction of Papua’s development. Initiated by the EcoNusa Foundation in collaboration with Kopernik, the event brought together central and local government officials, academics, civil society organizations, and indigenous representatives to discuss restorative bioeconomy as a middle path between economic growth and ecological sustainability.

In his opening remarks, Maryo, Regional Head of the EcoNusa Foundation for Papua, emphasized that restorative bioeconomy is the way to ensure Papua’s development does not come at the expense of its environment and indigenous peoples. “This concept has been discussed since the 1960s. But now we are facing an increasingly urgent situation, where the extractive model has proven to benefit only a handful of parties while leaving ecological destruction behind,” he said. He added that EcoNusa’s joint research with Kopernik highlights the extraordinary potential of this approach. “In the next two decades, a restorative bioeconomy has the potential to surpass the extractive economy, provided that we collectively support it with the right policies.” He also highlighted the achievements of nine indigenous cooperatives that in the past six months have generated revenues of USD 2 million. “Our target by the end of the year is USD 4 million. This proves that restorative economy is not merely a concept but a tangible practice that delivers results,” he stressed.

Similar support came from the local government. The Regional Secretary of Southwest Papua Province, Drs. Yakob Karet, M.Si, underscored the importance of positioning indigenous peoples as the main actors in development. “Indigenous communities are not objects; they are subjects of development, because their knowledge and local wisdom have been tested and proven to maintain harmony with nature,” he said. He outlined four pillars that must serve as a reference: protecting forests and ecosystems, strengthening indigenous land rights, developing alternative economies such as non-timber forest products and ecotourism, and creating economic value without damaging the environment. “If these four pillars are upheld, Papua can move forward without losing its identity, culture, or natural wealth,” he added.

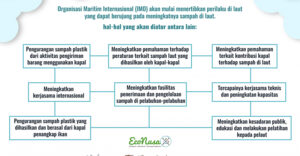

The central government, through Bappenas, also provided a broader perspective. Leonardo Adypurnama Alias Teguh Sambodo, representing Bappenas RI, highlighted Papua’s strategic position both nationally and globally. He explained that Papua is home to more than 20,000 plant species, 87 percent of the world’s endemic orchids, and 3,000 species of fish, placing it among the world’s biodiversity centers. “This wealth does not belong to Papua alone but is a national asset that can serve as the backbone of Indonesia’s bioeconomy,” he said.

Leonardo further noted that biodiversity issues have been integrated into the National Long-Term Development Plan 2025–2045 and the Papua Development Acceleration Master Plan 2022–2041. He emphasized that bioeconomy must be seen as a dual strategy: driving economic growth of up to eight percent by 2029 while ensuring ecological sustainability. “Papua must become the engine of Indonesia’s national bioeconomy. But we must also be honest: serious threats such as land conversion, pollution, and the marginalization of indigenous communities are real. That is why the key is inclusive collaboration, with indigenous peoples as the main actors, not just beneficiaries,” he concluded.

After the keynote speeches and policy outlines, the workshop moved into deeper analysis. The first panel discussion opened with a series of data and academic studies offering a picture of Papua’s current situation and the paths it might take in the future. In this session, participants were invited to view Papua’s development not only through the lens of growth figures but also through its impact on forests, indigenous communities, and long-term economic resilience.

Sita Primadevi of the World Resources Institute (WRI) presented projections through 2050. According to her, if development continues along a Business as Usual trajectory, Papua’s GDP will indeed grow, but forest cover will decline drastically, carbon emissions will rise, and indigenous communities will lose food security. “Macroeconomic growth does not always translate into indigenous welfare. This is the development gap that we must address,” she stressed.

From a macroeconomic perspective, Jaya Darmawan of CELIOS added a fiscal dimension. He argued that without innovative financing instruments, a restorative bioeconomy will be difficult to realize. “We need the courage to implement carbon taxes, windfall profit taxes, biodiversity taxes, and even wealth taxes. Without these, restorative models will not be able to compete with extractive industries,” he explained. He emphasized that restorative economy is in fact more promising, as it could generate over two trillion rupiah in output and create 35 million jobs within the next 15 years. This data provided a concrete response to WRI’s concerns about inequality in development outcomes.

Kopernik then demonstrated the tangible face of this potential on the ground. Chandra Dewanto presented the results of mapping 38 grassroots organizations in Papua. “Currently, the restorative economy is valued at around IDR 1.3 trillion. But by shifting just 30 percent of agricultural labor into restorative practices, its value could surge to IDR 130 trillion. The potential absorption of indigenous Papuan workers exceeds half a million people,” he explained. He stressed that success depends on strengthening community capacity, ensuring access to financing, and recognizing customary land rights. Thus, Kopernik’s findings illustrated how projections and fiscal tools can be translated into real practices at the village level.

If the first panel encouraged participants to examine data, projections, and policy instruments to support restorative economy, the second panel shifted the focus to actual practices on the ground. This session showcased how the broad concept of restorative bioeconomy has been translated into indigenous initiatives, cooperatives, and local enterprises already in operation. These stories revealed that Papua not only holds potential but also has tangible evidence that sustainable economies can thrive and provide direct benefits to communities.

Angelius Mangatasi Nababan from Mitra BUMMA shared the story of BUMMA Namblong in Jayapura Regency. “BUMMA is an indigenous-owned enterprise managed entirely by local clans. With a territory of more than 52,000 hectares, we have succeeded in keeping our forest intact with zero deforestation. At the same time, the indigenous economy circulates, generating 5.5 billion rupiah annually at relatively low management costs,” he explained. He added that the principle of Menoken, Membumi, Membumma—weaving solidarity, restoring the land, and building indigenous economic sovereignty—forms the foundation of this movement.

Etik Mei Wati from KOBUMI added a similar experience through a network of cooperatives in Papua and Maluku. “We manage commodities such as nutmeg, copra, cloves, shrimp, and tuna. Our targets for 2025 are ambitious—for example, 400 tons of nutmeg and 25 tons of tuna. But all of this is carried out by local communities under sustainable systems,” she said. She emphasized that profits are returned to communities through cooperatives, reinforcing the idea that restorative models grow strongest in collective structures.

The Ebier Suth Cokran Cooperative provided another perspective through agricultural innovation. Flandy Roberti Botto explained, “We shifted from monoculture cocoa to dynamic agroforestry. The result is not only diversified harvests but also healthier soil without chemical fertilizers.” He added that all workers are indigenous Papuans. “We have penetrated international markets, exporting to Europe and America, with premium prices for our organic products. This proves that Papua can compete globally,” he said. This story bridged local potential with international markets, further illustrating that restorative bioeconomy can stand on equal footing with modern economies.

Despite these achievements, speakers acknowledged the challenges that remain. Overlapping regulations, neglect of indigenous rights in licensing processes, limited community capacity to manage investments, and the lack of involvement of youth and women were identified as major hurdles. Recommendations emerging from the discussions included harmonizing regulations, strengthening indigenous institutions, enhancing community capacity, adopting appropriate technologies, and fostering multiparty collaboration under the pentahelix framework.

The workshop concluded with a shared commitment to develop a concrete action plan with short-, medium-, and long-term horizons. In the first two years, efforts will focus on strengthening community capacity and harmonizing policies. In the following three to four years, attention will turn to developing ecotourism and non-timber forest product industries. By the fifth year, restorative bioeconomy is expected to become the main model of development in Papua.

The entire gathering underscored one overarching message: Papua is the heart of Indonesia’s bioeconomy. With its unparalleled biodiversity and indigenous communities as its primary stewards, Papua holds immense promise to become a model of sustainable development that balances ecology, culture, and prosperity. As Nur Maliki Arifiandi from the Coalition for a Grounded Economy (Koalisi Ekonomi Membumi) emphasized, “Restorative bioeconomy is Indonesia’s future. From local initiatives, we must build it into a national movement that stands with both people and nature.”